|

|

|

Last time: In the previous entry of our trip log back to 1761 and the Cambridge Patent, we stopped one hundred years ago in 1911.

Chapter V: 150 Years Ago – 1861, Civil War and the Heroes of Washington County In recent years, the events and personalities of WWII have generated a host of books on that chapter of our nation’s story, likely surpassing now the previous trendsetters in published works, the American Civil War and its ancillary topic, Abraham Lincoln. The tragedy of 1861-65 has produced more than 50,000 titles with over 16,000 volumes written about the 16th president. Area authors have contributed with valid histories of the citizens of Washington County who marched, railroaded and sailed south to the mid-Atlantic and beyond, beginning in the spring of 1861, in the quest to save the Nation from fracturing over States’ rights and nullification, but more legitimately over slavery. Lincoln had been elected president the previous November by slender popular and electoral margins, which drove South Carolina, its sacred institution of slavery at stake, to declare five days before Christmas, “We’re outta here”. When Kansas Territory, after years of blood feud, attained statehood in January of ‘61 and swelled the Free State count to 23, the other Southern States followed suit. Eleven forged the Confederacy while the North begged to differ. President James Buchanan sat on his hands through his single term, so after Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1861, the new exec brought the hammer down. In April he declared the Rebel action illegal and appealed for Union Volunteers from all States still loyal to the ideal of one nation under God. In Old Cambridge 1788-1988, Mike Russert gives us “Our Sense of Duty: The Civil War Years”, revealing the units and leaders from the surrounding villages and farms who mustered into various New York Volunteer infantry, cavalry and artillery companies (later paid bounties to enlist.) The Southern coastline lent itself to key sites for offensive posturing by the opposing forces. Fortress Monroe, at the tip of the Virginia James-York Peninsula, commanded the Chesapeake and never fell to the Rebels; from there the US Army began one of its pincer drives into Dixie while the Navy embarked on its Anaconda Plan of strangling the Southern ports. But Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor was vulnerable and in April of 1861, exactly fifteen decades ago, the torch was lit. When the US commander didn’t strike the Stars-and-Stripes, his detachment took a pounding for more than a day before surrendering. Telegraph keys buzzed the news from Carolina to D.C. to upstate New York, from Maine to mid-country. As wires weren’t strung to the West Coast until December, it took the Pony Express to get the news quickly to Sacramento. So it began. The US Census of 1860 recorded 31 million citizens, plus four million slaves, mostly in the South. Russert recounts that Cambridge registered 2,419 folks, White Creek 2,802, and Jackson 1,863, farmers and millers, merchants, doctors and lawyers. Tanners, blacksmiths and wagon wrights also worked the shops along the commercial strips. Many had made their way into the area via the turnpike from Lansingburg and the Troy & Rutland RR passing through the Valley since 1852. This spurred growth at the hands of sawyers and carpenters, new homes raised through mid-century at, for example, 120 West Main Street (1840) and 1 Gilmore Avenue (1880). Buildings in town still standing that went up in 1861 include the Porter-Copeland dry goods & grocery (today’s Alexander’s Hardware); and the brick building on the corner of Main and Washington, the long time Cambridge Valley National Bank.

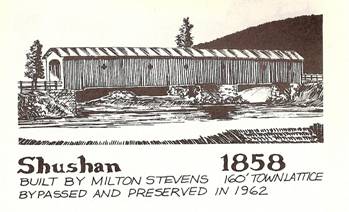

In early June of 1861 the first unit assembled in Cambridge was Company D, New York 22nd Infantry Regiment. Some crossed the three-year-old Shushan Covered bridge over the Batten Kill.

Upstream at Eagleville a large mill turned raw wool into blankets for the Union forces. The 22nd assembled in Troy for a two-year hitch, for what was imagined at the outset to be a mere 30-day battle in the fields of Northern Virginia. In late June Cambridge Company D, led by Capt. Henry Milliman, Lt. Thomas B. Fisk, and Lt. Robert Rice, traveled with the 22nd Volunteers to Washington to join the Army of the Potomac. Company D was assigned garrison duty in the nation’s capital throughout ‘61, but the next year fought valiantly at Second Bull Run, Anteitam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Of 26 officers and 600 men, the 22nd New York catastrophically lost as killed, wounded or missing 23 officers and 157 troops. Lt. Fisk was wounded, but Capt. Milliman fell in battle as did Clarence Coulter (namesake of a leading 20th century Cambridge citizen, remembered by readers today.) When Company D returned home in June 1863, they were given the heroes’ welcome, a parade of marching bands and fire departments, banners, cheering crowds and dinners. Then they fell into rank to perform close-order drills to the delight of the townfolk. One other Volunteer unit raised in Cambridge in 1861 was Company G of the 93rd New York Infantry Regiment. It joined other companies from upstate NY, and in December John S. Crocker of White Creek – a Cambridge educated attorney who sat on the NY State Bar – was commissioned colonel and given command of the 93rd. The Blue Jackets mustered in Albany early the next year, then transferred to Monroe where they served in the Peninsula Campaign and other battles, including Gettysburg in July ‘63. Col. Crocker made it home but in poor health from the effects of wounds, malaria and imprisonment in Dixie, yet after his discharge he was honored with promotion to Brigadier General and lived another 25 years to age 74. As the War dragged on other units were organized in Cambridge, including companies for the 123rd Infantry (Sept. ‘62) and the 16th Heavy Artillery (June ‘63).

The 123rd was recruited exclusively from the county and called The Washington County Regiment, led by Col. Archibald McDougall of Salem (MacDougall offspring, alternate spelling, are found today at Hedges Lake.) Company G enrolled men from Jackson and White Creek, including Lt. Jerome B. Rice, while Cambridge men registered into Company I. Al Cormier discussed the 123rd in The Eagle a few weeks ago, and Russert’s chapter in Old Cambridge 1788-1988 gives more details of all units raised locally during the Rebellion. Col. McDougall was KIA in 1864 during Sherman’s advance on Atlanta, and for Cambridge soldiers, a total of 46 died on Civil War battlefields, remembered in monuments of stone in Woodlands Cemetery and down at Gettysburg. While brave men marched off to fight, many to die, life went on in Cambridge. New residents included births and immigrants, while others were laid to rest with war raging hundreds of miles beyond the horizon. Over the hill in Greenwich, Anna Mary Robertson was two months old when Lincoln was elected; we knew her as Grandma Moses. Anna Coulter, kin to the fallen soldier, was born in 1861, first child of James and Jeannette Coulter. Irish farmer James Boland arrived in America around 1861, was married in St. Patrick’s Church, and had eleven children with wife Catherine, also a transplant from Eire. Charles Cassell was born this year, second child of Scot immigrant Thomas Cassell and wife Agnes. Vianna King died in 1861 third child of Solomon King, granddaughter of William King, both veterans of the Revolution with the Dutchess County Militia. They’d faced the Redcoats at the Battles of Long Island and White Plains, and in 1792 the elder bought land in Cambridge and moved his family here. By mid-war, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address of late 1863 harked back “four score and seven years”, not to the birth of the Constitution in 1787, but to July ’76 and the Declaration of Independence. That first sheepskin, our Dear John to King Charles, declared all men equal, individual men. The new US Law, though, decreed those in a certain class “3/5ths a man”. This wasn’t to diminish the rights of any individual but to grant equal rights to the whole, to normalize political representation. If slaves were uncounted (as were the Indians), the Northern industrial States would overwhelm the new US Congress. But if a Black registered as “one whole man”, the agrarian South would rule. On the surface, simple arithmetic, nothing aristocratic, nothing sinister by the white Christian and Deist Founding Fathers, unless agenda overrode the ideal, including possible selective reading of Scripture. But to Mr. Lincoln, the first manuscript trumped the second as the former invoked God and Judeo-Christian ethics to guide the national conscience while the latter document does not, given its secular design of favoring no Faith. Yet had Lincoln not been sworn in by 1861, consider the fodder for historical novelists: How many more years, decades, might it have taken for our Glorious Republic to move beyond its 80-year blemish-faced adolescence to achieve a measure of social maturity?

In your formative years as a child you noticed events of the day that framed your worldview: the Korean War, JFK’s death, the lunar landings, Vietnam, Watergate, the fall of The Wall. Those born in the 1850s were likewise shaped by the Civil War, including two future presidents, Taft (1909-13) and Wilson (1913-21). Giants of medicine Walter Reed and William Mayo, both born the decade before the War, later worked to end diseases that ravaged Yank and Reb alike, ills that killed more than the Minie ball. Captains of industry C.W. Post (breakfast cereal), F.W. Woolworth (five and dime), and Charles Dow (business journalist) rose to fortune on the wings of the Gilded Age, leaving us enduring institutions; and painter and sculptor Frederic Remington gave us the post-war drama of a romantic American West. Matthew Brady was an adult, though, when he paced the killing fields of the 1860s to record his chilling and historic images, paired with journals by the hardened veterans themselves, including the memoirs of U. S. Grant, published by Mark Twain. Only a matter of time before sixty thousand texts filled our bookshelves. In America’s wars since, evolving technology continues to splash cold water in our faces, from the Movietone newsreels of WWII, to the TV set that brought distant rice paddies into our living rooms, to today’s webcam windows into remote desert civil wars. The Fourth Column marches on in the Free West with fair and balanced journalism’s inroads forged into other cultures day by bloody day. Yet freedom isn’t free (says the bumper sticker), so we continue to strive with firm resolve toward a hopeful peace in our time, or that of the grandkids of the Cambridge District of 2011.

Next time: Chapter VI: 200 years ago – 1811, The New Nation and a Second War for Independence

Sources: Old Cambridge 1788-1988; New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center; The Eagle Newspaper; illustration, Bob Raymond; photo, Tom Raymond

Correction: In Chapter I (1961) the Captain of the CCS Indians Varsity Basketball team was identified as Bill Nygard, who was actually Co-captain with Donnie Vitello The author may be contacted at: tmraymond4@gmail.com

======================================================================== CAMBRIDGE HISTORY LIVES © 2011 Thomas M. Raymond

|