|

|

|

Last time: A few columns back we discussed the Cambridge Patent of 1761, then stepped forward through the following decades to the Revolution, the Constitution, and the new American Presidency. We’d also stopped along the way to sketch events of Cambridge and America in the years wrapped around 1811 and 1861.

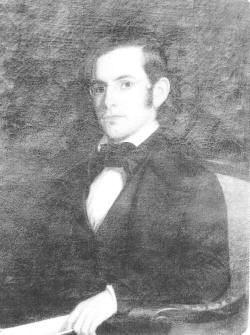

Chapter 16: Early-Mid Nineteenth Century, Forty Festering Years – 1820s-1850s, Part I We’ll soon visit the post-war years beginning in 1866 after Johnny came marching home, but first let’s infill the forty years that festered like an infected wound and led to that great national tragedy. The fourth U.S. Census in 1820 registered over 9.6 million citizens, with more than 1.5 million legal slaves picking cotton and subject to the bullwhip. American Black liberation was basically born in this decade. The year prior, Alabama had joined the USA as the 22nd state while the Panic of 1819 spread across the land, one of the harsh economic set-backs of the 19th century. It was set off by large debt from the War of 1812-15, by private western land speculation, and by over-investment in manufacturing. Unsecured credit and national banking politics led to devalued paper currency no longer redeemable in precious metals. Thankfully new federal banking policies eased the crisis by curtailing credit and standing hard on debt (a good lesson for today?) While the banking system of the 1820s was salvaged, many in the South and West were ruined. Yet in the Northeast commerce got a boost as the Champlain Canal opened from the Hudson River at Fort Edward to Lake Champlain, a venture envisioned by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison during their trek through our region in 1791, which included a stop at Colvin’s Inn in Cambridge (a site uncertain, only theorized today.) With covered wagons rumbling ever westward down along the Ohio River Valley, and new farming tracts opening at a record pace beyond the Mississippi, the slavery question was hotly debated. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 sought to keep the peace by maintaining the nation’s free-slave balance, with free Maine becoming the 23rd state (spun from MA) and slave Missouri, the 24th (1821). This merely delayed the inevitable for another few decades, i.e. rebellion and civil war. In 1823 President James Monroe, in office since ’17, issued his Doctrine, essentially banishing Europe from new forays into the hemisphere … perhaps not unlike Stevie Nicks telling Joe Walsh, as crooned by Tom Petty, “Don’t come around here no more”. (Ms Nicks, however, likely dozed through that HS history lesson.) In 1820, after a lifetime of steadying influence in the birth of the new republic, John Jay, age 84, passed into history. Five years later, John Quincy Adams, son of the second president, was inaugurated the sixth Chief Exec. The next year, on July 4, 1826, ironically yet very historically John Adams, age 91 (at Quincy, MA) and Thomas Jefferson, 83 (at Monticello, VA) died peacefully in their sleep within a few hours of each other … on the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Fellow patriots in the quest for freedom, Adams and Jefferson had been intense political rivals but later, through correspondence, were great friends to the end. It’s said our National Holiday, as celebrated today with patriotic pride and pageantry, had its birth on this very day. (In 1870, Independence Day became an unpaid day off for Federal employees and, in 1938, a paid Federal holiday.) Locally, in 1824 the Rensselaer School (later Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, RPI), was founded in Troy as one of the nation’s prestigious engineering schools. Construction of the Erie Canal was soon completed, and foodstuffs and manufactured goods from the Great Lakes region began flowing into the Albany area and found their way into Cambridge markets and stores. In 1826 the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad - Albany to Schenectady - became the first railroad chartered in New York State, and the first railroad in the nation to be driven by a locomotive piston engine, rather than be horse-drawn or gravity powered. The next year, 1827, the first successful covered bridge in the immediate area, the Eagle Toll Bridge, was built over the Hoosic, upstream from Buskirk’s Bridge at (later-named) Eagle Bridge. It survived for over eight decades, until 1898. In 1829 Andrew Jackson, “Old Hickory”, was sworn in as the seventh US President; Jacksonian Democracy took root, a voice “by a common man for the common man.” In 1831 James Monroe, 73, passed away less than six years after leaving the high office. After a dozen years of construction, Fortress Monroe, VA (later Fort Monroe) was completed in 1834, the largest stone-masonry fort ever built in America. It commanded (still commands) the entrance to Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic and served to protect Washington D.C. against a repeat of the 1814 disaster at the hands of the British. The durable old fort on Old Point Comfort, still with the nation’s only active water moat, was turned over not long ago by the U.S. Army to civilian authorities to be developed into a public historic park. In 1836, James Madison, age 85, passed away, the last survivor of our remarkable Founding Fathers. Over the next 30 years, from 1830 to 1860, the U.S. Census ramped from 12.8 million, including two million slaves, to over 31 million, with almost four million in forced service to the gentry of the land - a land with supposedly only one class of citizen. While the nation’s population center continued to gravitate west during this period, 30,000 more miles of railroad track were laid, mostly in the East and mostly of poor construction. The rails and trestles were prone to failure, proving time and again deadly to passengers and crew. “Let the traveler beware”, wouldn’t fly today, of course. The Old White Church was built in Cambridge in 1832 to replace the 1793 First United Presbyterian Church on the same site on the NE corner of Main and Park. By 1839, the first Roman Catholic Mass in Cambridge was held in a private residence. Significant to the development of the Cambridge Valley during the 1830s was the McCormick reaper, invented in VA in ’32, the first of two such breakthroughs for modern agriculture. The second invention was the perfection of the John Deere steel plow (in IL) in 1836, made to till particularly hard and stony terrain. Ask any local farmer about the Owlkill soil as anything but finely grained fertile alluvium. Local and nearby city papers likely carried the tale in the 1830s of American pioneers who were invited by the Mexican government to settle its northern tracts - acquired from Spain a decade earlier - when its own people refused to migrate above the Rio Grande to eke out a living among the jackrabbits and sage. Soon the Anglo population outpaced the Hispanics and the former tried to declare independence. “Not so fast”, interjected Generalissimo Santa Anna who in 1836, with his Napoleonic inspired and festooned army of several thousand, defeated a ragged band of American patriots led by Col. William B. Travis, Jim Bowie and either Fess Parker or John Wayne at the Alamo. Sam Houston’s Texicans then drove the temporary victors back to Mexico City, creating a Free Texas. But a decade of new tensions smoldered along the Rio Grande, yet long before “mules” packed, not with corn, but contraband: drugs and guns. These future illegal aliens and voters (aka “undocumented Democrats”) would pick up their mops and buckets and (to be invented) leaf blowers at their local Ace Hardware stores stretching from sea to shining sea across their new land of plenty (of government handouts.) Back in 1837, a political struggle between factions for a single Federal bank vs. private money institutions triggered a four-year national recession after a panic. Banks held next to worthless mortgages when President Jackson ordered public land sales in silver or gold only, no paper currency. Many Americans across many types of businesses lost their life’s savings, including Brooklyn milliner (hat maker) Eliakim Raymond II. Fortunately, his son Robert Raikes Raymond (see the portrait) was enrolled during these years at Union College in Schenectady (officially chartered in 1795). He graduated in 1837 and forged an early career as journalist and attorney, and later as preacher and abolitionist, helping to run an underground railroad shelter near Syracuse, while rubbing elbows with the likes of the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and Frederick Douglass. His portrait hung on the library wall of 120 West Main Street, Cambridge, from 1920 to 1972, and today is in the possession of Union College, a gift from the Raymond family a few years ago. (More on that later.) During the panics of 1819 and 1837, debt was called in by the strong-armed, unlike today when we’re more “civilized” and don’t toss people out in the streets (mostly), where sky’s the limit for debts and deficits, and trillions the word of the day. $6T is likely going on 16, if we continue the course America was assured four years ago, one of “hope and change.” But today we “reassuringly” hear, “The Buck Stops There”.

Next time: Chapter 17, Early-Mid Nineteenth Century, Forty Festering Years – 1820s-1850s, Part II Sources: A History of the Cambridge Area (R. Raymond, T. Raymond 2010); Ken Gottry Jr.; Union College (The author may be contacted at tmraymond4@gmail.com. |

|

CAMBRIDGE HISTORY LIVES © 2011

|